Disability Advocates Urge Support for Emergency Funding Bill to Address Medicaid Care Crisis

Washington, DC – Every person deserves the freedom of living in their own homes, being a part of their communities, and choosing how they spend their days. Medicaid’s home and community-based services makes that possible for millions of people with disabilities and older adults, yet chronic underfunding is forcing them into institutions and putting families in crisis. Today, the Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) Relief Act was introduced by Senator Bob Casey (D-PA), a bill that would provide emergency funding to state Medicaid programs and have a profound impact on disabled and older Americans. The Arc applauds this pressing bill and urges lawmakers to pledge their support for independence and inclusion.

“Marginalized for far too long and facing catastrophic shortages of direct care workers, people with disabilities and their families are desperate for help,” said David Goldfarb, Director of Long-Term Supports and Services Policy at The Arc of the United States. “Without access to basic support for daily living, disabled people are at risk of being confined, isolated, and neglected in institutions or trapped in their homes. This is about the basic human right to live in the community. It’s time that we show people with disabilities that their lives not only matter, but that they are valued members of our society. The HCBS Relief Act would support and strengthen their daily lives, while also improving health, economic stability, and quality of life for their families and direct care workers.”

Millions of people rely on HCBS for daily activities, such as dressing, bathing, meal preparation, taking medication, employment support, mobility assistance, and more. The HCBS Relief Act would provide dedicated Medicaid funds to states for two years to stabilize their HCBS service delivery networks, recruit and retain HCBS direct care workers, and meet the long-term support and service needs of people with disabilities and older adults. The HCBS Access Act, which was introduced in March 2023, would make a transformational impact on the care crisis, but emergency relief is needed right now, which this bill would provide.

“My disability means I need assistance getting around and sometimes with communicating,” said Steve Grammer, a Disabled Self-Advocate living in Virginia. “When I was 22, my mom fell ill and I was placed in a nursing home. I got to see her just once before she passed away. After 9 long years, my dream of independence came true. With the help of in-home caregivers, I have my own apartment and I can choose what I want to eat, where I want to go, and what I want to do. I no longer worry about my food being served cold or my medications being administered late. I can stay out late with friends while we listen to our favorite bands. I have freedom—and a life like yours. I’m living proof that people who have been barricaded away can live on their own and thrive while contributing to their communities.”

“I started out in an institution,” said Veronica Ayala, a Disabled Self-Advocate living in Texas. “I was there for 18 really long months, and I was a child, so that was really traumatic. For 18 months, I didn’t have my mother to put me to bed, tell me a story, give me a bath. There was no love or attention given. Thankfully my mother realized that she could do it on her own with home and community-based services. With the right supports, anyone with a disability can live in their community. Anyone with a disability can succeed.”

Recent research from The Arc and the University of Minnesota shows that 35% of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) are trapped on waiting lists for supports and services they desperately need, 19% of which have been waiting for more than ten years. This doesn’t just impact their lives – it’s having a ripple effect on their families and our economy. Nine in ten family caregivers reported that their careers have been negatively affected due to a lack of supports, and 66% have had to leave the workforce entirely. This is ultimately leaving families significantly stressed and financially strained.

###

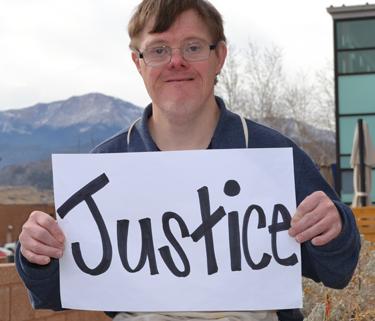

About The Arc of the United States: The Arc advocates for and serves people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), including Down syndrome, autism, Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders, cerebral palsy, and other diagnoses. Founded in 1950 by parents who believed their children with IDD deserved more, The Arc is now a network of nearly 600 chapters across the country promoting and protecting the human rights of people with IDD and actively supporting their full inclusion and participation in the community throughout their lifetimes. Through the decades, The Arc has been at the forefront of advances in disability rights and supports. Visit www.thearcwebdev.wpengine.com or follow us @TheArcUS to learn more. Editor’s Note: The Arc is not an acronym; always refer to us as The Arc, not The ARC and never ARC. The Arc should be considered as a title or a phrase.

Today, Pathways to Justice remains one of the few IDD-specific programs in the US. It has reached over 2,000 stakeholders in over 12 states and has created Disability Response Teams around the country, creating sustainable change.

Today, Pathways to Justice remains one of the few IDD-specific programs in the US. It has reached over 2,000 stakeholders in over 12 states and has created Disability Response Teams around the country, creating sustainable change. NCCJD’s programmatic work must evolve and remain innovative as we seek to reform a criminal justice system that too often remains unaware of the unique needs of the IDD community. We are revisiting our strategic plan and the Pathways program to include the most up-to-date research, best practices in curriculum delivery, and effective ways to incorporate a lens of intersectionality by grounding the work in a disability justice framework. The updated Pathways will include a more robust technical assistance program focused on helping DRTs set achievable goals to begin a community’s path on sustainable change.

NCCJD’s programmatic work must evolve and remain innovative as we seek to reform a criminal justice system that too often remains unaware of the unique needs of the IDD community. We are revisiting our strategic plan and the Pathways program to include the most up-to-date research, best practices in curriculum delivery, and effective ways to incorporate a lens of intersectionality by grounding the work in a disability justice framework. The updated Pathways will include a more robust technical assistance program focused on helping DRTs set achievable goals to begin a community’s path on sustainable change.